April 2006

Dog Noses Know

New Canine Tools for Detecting Cancer

by Pete Alexander

Health is very important to all of us, and in order to maintain it we need early and accurate diagnoses of anything serious, like cancer, that might jeopardize it. The medical profession has at its disposal very costly and extremely accurate high-end scanners to detect very small numbers of cancer cells. However, these wonderful tools do not always find all cancers. There is, however, a new kid on the block, who can possibly help where scanners cannot. Is this kid a dog? How did you guess?

Impressive claims from San Anselmo

Over the years we have heard reports of dogs who have sniffed moles on humans, or human breath, very intently, humans who later were diagnosed with cancer. When I returned from a hospital stay after a surgical procedure that left remnant amounts of blood in my leg, my dog Linda Lou immediately began to sniff that leg for five minutes at a time. The condition subsided within two weeks, during which time she became gradually less interested.

A June 2005 CBS “60 Minutes” report covered a man whose dog Trudi sniffed a mole on his leg that later turned out to be malignant melanoma. Once the cancer was removed, Trudi confirmed with her nose that it truly was gone.

In a comment on http://www.worldchanging.com , Ilsa Ponte wrote about her dog Tucker, who spends a lot of time with her mother. “[My mother] started noticing every night when she would sit down to get undressed the dog (Tucker) would be right there, always smelling her left breast, he never tried to smell any other part of her body. We laughed and didn’t think anything about it. She went in to have her first mammogram at 63, not because of the dog but because the doctor ordered it. She did have breast cancer. After she had her surgery to have her breast removed, he never smelled or bothered her when she was undressing.”

A San Anselmo organization called the Pine Street Foundation runs the Pine Street Clinic, directed by Michael Broffman. The Clinic conducted a scientific study using dogs provided by Guide Dogs for the Blind in San Rafael, the results of which show that dogs can, after a relatively short period of training, detect cancers of the lung and breast with a very high level of accuracy. Study results will be published in Integrative Cancer Therapies (March 2006, Vol. 5, No. 1).

Against conventional wisdom

Many in the scientific community cry “poppycock” at the notion that dogs can detect cancer. Some argue that all the smells of a human, whether cancerous or not, would overwhelm a dog’s olfactory receptors (New York Times, Jan. 18, 2006). Julian Guthrie reported in 2003 in a San Francisco Chronicle article, “Dr. Wallace Sampson, editor of the Scientific Review of Alternative Medicine, and a member of the Board of Directors of the National Council Against Health Fraud, laughed when told of the concept.”

Well, it does sound a bit far out, right? But the facts are that dogs’ sniffers have 1,000 more receptors than those of humans and can detect their sense of smell is 10,000 to 100,000 times more powerful than ours. Why not at least study the potential? That’s where the Pine Street study comes in.

Nose vs. machine

CT scans produce many false positives (which can be reduced through an additional scan using positron emission tomography scans), results that can, and do, lead to unnecessary biopsy surgeries. Mammograms are not perfect either. But can dogs help out?

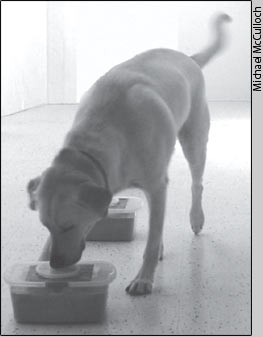

In Broffman’s research, dogs identified breast and lung cancers with respective accuracy rates of 88% and 99%. The Pine Street study focuses on 170 people: 83 of them cancer free (“control patients”), 32 with breast cancer, and 55 with lung cancer. First, five dogs from local owners and Guide Dogs for the Blind were trained using the clicker and treat method. They were rewarded when they found the right odor from among the identical pots. This training phase took only two to three weeks.

Next, researchers gathered breath samples from 26 breast cancer patients, 27 lung cancer patients, and 66 controls. The tubes containing the samples were put in plastic boxes and numbered. Each dog got the command to “Go to work,” then walked past and sniffed each sample (the tubes placed in an 8” well to prevent nose contact). When the dogs encountered a positive sample, they were to sit. Of five samples in both the single- and double-blind tests (meaning neither dog, dog handler, nor tester knew which samples were which), only one was positive for cancer. After each test run, the samples were moved around, the positive sample randomly placed. The remaining 28 lung cancer samples, 6 breast cancer samples and 17 controls that were not previously sniffed by the dogs were used in the part of the study for “double blinded testing.”

You want results?

Results? 564 times out of 574 tries with lung cancer-identified samples, the dogs were correct. With breast cancer-identified cases the dogs were able to correctly identify the cancer 110 of 116 times. Overall sensitivity of canine scent detection for lung cancers was .99, and for breast cancer samples .88, (comparable to mammogram results). What about the healthy peoples’ tubes? The dogs sat 4 out of 712 times.

What’s next? Researchers at the Pine Street Clinic propose more studies to resolve the uncertainty about whether differences in patients’ diets could change breath odors to the point of interfering with the dogs’ accuracy. Further, they want to combine and compare canine scent detection and current analytical chemistry methods to determine optimal diagnostic applications for each method.

In fact, they have already for applied for funding to compare standard testing with canine sniffing by comparing mammogram and breath analysis results for women who are being tested for breast cancer. They also plan on studying women being tested for ovarian cancer, working with Professor Touradg Solouki and his team at the University of Maine.

The Pine Street team hopes funding will come through this summer; the study would take a year, so look for results in summer of 2007. The idea, Foundation Director Michael McCulloch says, is to marry canine sniffers with standard testing to get the best result. If two tests are positive, it vastly increases the likelihood of a true positive result.

What does it mean for us? It means that our canine friends may someday be trained to add a significant health support role to their awesome repertoire of playing, romping, eating, snuggling with us, and taking us for walks. If your dog is sniffing you a lot, what she is after most likely is possibly the scent of another dog or a cat, or maybe you should have put a napkin on your lap while eating lunch. However, if her nose is insistently and often pressed against a mole or your breath, even possibly looking up at you between sniff s, you might pay heed and have it checked out. Pine Street has no current plans, however, to study my final question: can dogs detect cancer in other dogs? Hey, first things first, right?