June 2006

A Day in the Life of...an Animal Control Officer

by by L. A. Craig

Once, the “dog catcher” was a feared and highly loathed member of the community. Today, the term is politically incorrect and Petaluma Animal Control Officer Jeff Charter spends his workdays trying to change the perception through word and deed. “Humaneness is what we do,” says Charter, who is senior officer with just 18 months on the job. “We exist so animals in Petaluma are cared for. And we’re lucky to be in this city where there’s a lot of support and not a whole lot of problems.”

At 8 a.m. on a drizzly Saturday, Charter’s first call is from

a woman guarding a possum which has

apparently been struck by a car. The woman stays on site to divert

traffic while Charter collars the animal, half-crazy from the pain

of a severe head wound, and places it in a compartment of his truck.

“We’ll have to put him down, so he won’t have to suffer,” the officer says. “Calls about possums are pretty rare and they’re usually DOA. If they’re not hurt, we release them. In this job you spend a lot of time helping animals live, and sometimes you have to help them die.”

On the way back to the shelter, Charter notes a big difference between his current job and his seven-year stint as a Sonoma County Sheriff’s deputy and jailer. “For the most part, when you show up, you’re welcomed,” he says. “As a deputy, people mostly didn’t want you to be there.”

It’s not a death sentence

Perhaps the biggest misconception about Charter’s job is what actually happens once an animal goes in the truck. Plenty of people view that as a death sentence. “The first thing people want to know is how long before we kill the animal,” he says. “They don’t understand what we do or why we do it. Any adoptable animal stays at the shelter until it’s adopted. One cat stayed more than two years.”

One difficulty in answering injured animal calls is that Charter must observe all traffic laws, including the posted speed limit. “We don’t have the same luxury as other enforcement agencies,” he says. “It’s very hard knowing that I have to take my time getting from the west side to the east side while a dog is lying in the street suffering.

“Once you get it to the vet, you have to make a decision about

how far you want to go. I have to make that call knowing that the money

for it comes from donations. I’ve never had to say ‘no’ yet.

But

we’ve also had to eat some heavy vet bills when the owner either

couldn’t pay or refused to. You just can’t recover that

money. Unless they have a history [of abuse or neglect], people get

their pets back anyway,” he adds. “In California, animals

are property. You can’t deprive people of their property without

due process.”

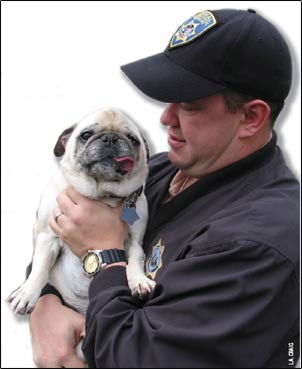

Charter also has the sometimes-distasteful task of periodically checking the welfare of animals whose owners were previously cited for improper treatment of their pets. Today, he’s making a call on a sweetheart of a little Pug who developed a serious neck injury from a too-tight collar, as reported by a neighbor, and developed maggots. A physical exam of the Pug shows his wound is healed and that he appears to have his basic needs, food, water and shelter, provided for him.

“We have powers of arrest, the same as a correctional officer,” Charter says. “We check out all reports. If there’s a history, we seize the dog and take it to the vet. Then we get a vet-care agreement from the owners. There are certain times when you have the right of entry.

“About 25% of complaints are unwarranted: personal problems between neighbors,” he says. “In one case, a dog looked just terrible, but we found out it had a serious medical problem and was being treated. We also get quite a few legitimate abuse cases. One of them is in felony court right now. It’s all covered by the penal code. I try to keep my heart out of it. When you personalize it, you lose your professional objectivity. But there are times when you have to look at people and say, ‘You should be ashamed of yourself.’

Catch me if you can

“We’re just trying to contain the animal and sometimes people chase it away because they don’t want us to catch it,” he says. “More often than not, I’m more afraid for the animal than for the people.” After the possum is taken from the truck, Charter hoses out the space with disinfectant to prevent cross-contamination.

He then proceeds on a call about a dog-mauled bird stuck in a garage. As it turns out, the bird has lost some tail feathers, but can fly and is considered “viable.” He opens the garage door and lets it fly away.

“My philosophy is that we don’t do enforcement as much as educate people. For example, when someone’s dog keeps getting out we check the fences to see how it’s getting out. Maybe there’s a break in the fence, or the dog’s been tunneling under.”

With intermittent rain causing a slow day, Charter makes the rounds of Petaluma’s parks and other outdoor areas to make sure all dogs are on leashes and that “everybody is playing nice. And if a dog is off leash and the owner doesn’t have one, I lend him one.” One excuse people use for not having a leash is that the dog is so small, who can it possibly hurt? “If the dog only weighs a couple of pounds, then they should have no trouble snatching it up when that big dog on the loose comes around the corner,” Charter says.

Among the many joys of Charter’s job are the many animals who get “redeemed:” recover from antisocial behavior and take their places as revered pets. “Some dogs come in mean and over-the-top aggressive, biting the chain link fences and growling at you. Sometimes I’m totally surprised when in four to six weeks they’re eating out of your hand. They’ve been hanging around people and getting fed and treated well. I don’t know the figures, but our rate of redemption is way above the national average.”

Seeing a lost pet reunited with its owners, sometimes after many weeks, is also a feel-good dividend. “We had a little Beagle for two or three months,” the officer says. “He had somehow gotten here from Santa Rosa. His owner had put ads in the paper and checked her local shelters. She came to Petaluma as a last-ditch effort and when she saw her dog, she just broke down.

“We interact with all kinds of people all over the city,” Charter sums up. “We get out to the schools and teach the kids when it’s safe to walk up to a dog and when it’s not. Get out of the truck and talk to people. We are facilitators for a lot of things. But people don’t care how much you know until they know how much you care.”