May 2006: Health Matters

Mitral Valve Insufficiency

It Can Break Your Pet's Heart

by Christopher Forsythe, DVM

Hello, readers. Welcome to Health Matters. My name is Dr. Christopher Forsythe. I am a small-animal veterinarian practicing in Sonoma. Each month I will contribute a pet veterinary care topic with the hope of tweaking your interest, making you smile, and educating you about your pets.

Chronic

mitral valve insufficiency (CMVI), one of many types of congestive

heart failure, is the most commonly seen cardiovascular disease in

dogs. Not a week goes by that I don’t diagnose a new case, and

as pets are living longer lives and the senior segment of our pet population

grows, there will be more cases of this difficult yet treatable heart

ailment. This month, I want to share with you my experience with this

disease, including clinical signs, diagnosis and treatment.

Chronic

mitral valve insufficiency (CMVI), one of many types of congestive

heart failure, is the most commonly seen cardiovascular disease in

dogs. Not a week goes by that I don’t diagnose a new case, and

as pets are living longer lives and the senior segment of our pet population

grows, there will be more cases of this difficult yet treatable heart

ailment. This month, I want to share with you my experience with this

disease, including clinical signs, diagnosis and treatment.

CMVI is a slowly progressive disorder in which the mitral valve between the left atrium and ventricle loses its ability to snap shut completely every time the heart beats. Since this valve, responsible for helping maintain the constant forward flow of blood out of the heart, is compromised, some of the newly oxygenated blood that should get pumped to the aorta and rest of the body is allowed to slip backwards and into the lung area.

Although CMVI may begin at middle age (five to seven years), clinical signs often don’t begin until the pooch is over 10 years old. The most common complaint for the disease is coughing. The cough is deep and resonant and usually worse at night or in the morning. The cough is likely due to congestion in the left side of the lung due to poor forward flow of blood through the heart.

Let’s get physical

The earliest physical clue is a left systolic murmur detected during routine examinations of a middle-aged dogs. As the disease progresses, this murmur becomes more intense and “holosystolic” which means it is longer in duration. With a stethoscope one can detect muffled heart sounds if there is fluid in the lung space, and lung sounds can vary with the severity of the disease. I advocate examining every pet every time.

X-ray vision

Once we get these clues, we take x-rays of the thorax to see if there

is pulmonary edema, or fluid filling up into the lung fields. Often

in older pets, the valve begins to thicken and become irregular, and

the resulting murmur leads to increased heart workload. The cardiac

muscle has to try harder to pump blood to the body, and the left side

gets larger. This enlargement also is visible on the x-ray, as is an

elevated trachea, pushed up by the enlarged

heart.

Cardiac ultrasound: a little transducer goes a long way

Ultrasound is one tool we use frequently to determine problem’s severity. In a pet with mitral valve regurgitation, ultrasound allows us to visualize “turbulent” blood flow in the left atrium and ventricle, meaning that blood is bouncing around rather than streaming fluidly.

How do you mend a broken heart?

Mitral valve regurgitation is not a curable disease, but it is treatable. Usually pets are treated as outpatients unless an animal is having severe breathing problems or presents with clinical signs such as vomiting that require hospitalization and stabilization.

ACE inhibitors, drugs that essentially decrease the workload of the heart, are very helpful to pets with left sided congestive heart failure due to degenerative mitral valve-disease.

Furosemide, also known as Lasix, is a diuretic that helps remove excess fluid in the lungs. It markedly helps pets who are coughing and having trouble breathing. As with all medications, this one requires your veterinarian to monitor kidney function and electrolytes carefully.

An ounce of prevention

Prescribing an ACE inhibitor early in the course of heart disease in patients with CMVI may slow the progression of the heart disease and delay onset of congestive heart failure. It is also wise to minimize stress, exercise, and sodium intake in patients with this disease.

Heart disease is in my own home

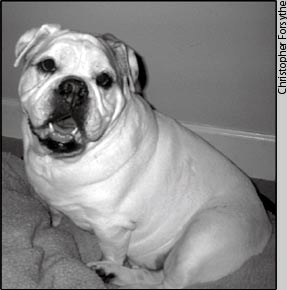

I really hoped it would never happen to my own pet. Mrs. Butterworth gave birth to 28 of the most perfect, adorable, and life-affirming bulldog puppies in the western hemisphere during her prolific maternal years. Four years ago she survived mammary cancer, and had a mastectomy after turning 10. Then at the age of 12, she started panting, sitting down on her walks, and coughing in the morning. I recognized the signs after placing my stethoscope on the left side of her pudgy, white, meaty chest.

Instead of “lub dub, lub dub” I heard “swish swish, swish swish.” A grade three (out of six) systolic murmur in Mrs. Butterworth, the Diva of Sonoma. It was like a splash of cold water on my face to realize this matriarch of the flat-faced breed was facing quite a serious challenge.

Blood tests, x-ray and ultrasound confirmed moderate mitral valve regurgitation with mild pulmonary edema. I immediately placed her on Lasix and an ACE inhibitor called Enalapril, and within two days she had the gleam back in her eyes, the swivel back in her hips, and the wriggle back in her adorable nub of a tail. Here’s hoping that nub will be wriggling for at least a couple more years to come.