May 2006: Well-heeled Dog

Wolves and Wolf Hybrids: Perfect for home, or for the wild?

by Trish King

Having a happy relationship with your dog means learning how to work together. If there´s a topic you´d like to see Trish cover, email editors@fetchthepaper.com.

Jim and I walked to his car as he explained his dog’s problems. He couldn’t seem to contain Yuki. She had figured out how to open doors and could scale a six-foot fence with ease. And she was monumentally destructive. This wasn’t puppy behavior; Yuki was almost three, and Jim still couldn’t trust her inside.

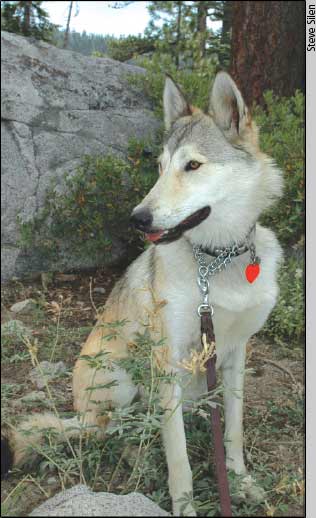

He opened the door of his SUV, and out jumped one of the most beautiful animals I’d ever seen. She was tall and well built, with very large ears and feet, not to mention teeth. Her chest was thin, her coat was thick and luxurious and her eyes a startling gold color. I looked at Jim. He grinned and said, “Yes, she’s a hybrid.”

Evolutionary, my dear Watson

The popularity of wolf hybrids waxes and wanes. Sometimes we’ll see quite a few in a year, sometimes none at all. It seems that most people get them for two reasons: they are as close as one can get to a “wild” pet, and they are gorgeous. However, hybrids do not usually make good pets. They are not dogs, and they are not domesticated in the true sense of the word.

To understand hybrids, it’s helpful to analyze how dogs became our pets. For years, it was thought that some prehistoric children brought home wolf puppies and begged their moms to let them keep them. But that was never a logical reason. It’s more likely that dogs domesticated themselves, as argued by Raymond Coppinger in his book Dogs: a Startling New Understanding of Canine Origin, Behavior and Evolution. His theory is that wolves began hanging around human encampments, waiting for whatever edible items people did not want. You can see this phenomenon today in third world countries where homeless dogs abound as scavengers, living on the outskirts of towns and villages. You might well wonder why these dogs, as well as our own domesticated dogs, look different than wolves. Scientists wondered too.

In an experiment in Russia that spanned years, wild foxes were selectively bred only for tameness. Over several generations, as the foxes became tamer, appearances changed: ears dropped, head shapes became more dome-like, and many started sporting spotted or blotched coats (sidebar). As they evolved, the appearance of dogs changed in the same way. In effect, they carried many of the characteristics of wolf puppies into adulthood.

Even though our dogs share wolf genes, they are far removed in evolutionary terms, according to Coppinger’s theory. Dogs were bred to do various jobs, like herding or hunting, and to rely on people for their sustenance.

Looking for a challenge?

Behavior ‘problems’ of wolves or wolf hybrids are actually the natural behaviors of a wild canid. The problems many people complain about are escape orientation, destruction, housetraining, predation, dominance, and unpredictable aggression.

Hybrids tend to want to escape for several reasons. They naturally have a territory of hundreds of acres. Our little patches of land are insulting! Due to their high intelligence, they seem to take our fences as challenges. One person I know has her hybrids enclosed within eight-foot fences with an electrically charged wire on the top. She has reinforced concrete at the base, so that her animals can’t dig out. Her female somehow managed to escape anyway and did what predators do. She chased some deer.

Dogs are predators too, but we have inhibited those instincts, so now most are more or less trustworthy. Instead of chasing and killing prey, for instance, a Border Collie chases and herds sheep. Wolves have no such inhibitions. They will chase prey, and they will be smart about it.

The destruction so many hybrids perpetrate on their environment wouldn’t be a problem in the wild, where a piece of wood isn’t part of a coffee table. Not only do wolves feel the need to experiment and exercise their jaws, they also can get bored with their understimulating indoor lives and begin chewing up our stuff as a result.

What about housetraining? Both male and female wolves in the wild do not eliminate where they sleep, but they do mark the perimeters of their core territories, and they do it often!

True aggression is rare, but many hybrids are not tolerant of human behavior, especially as they reach social maturity. They do not like to be hugged or approached too quickly, and will sometimes show displeasure by snarling or growling. In our society, we call this aggression, and we often punish for it. This can then lead to more aggression as the animal defends itself. Inconsistency in the human/canine social order can also lead to aggression.

Finally, as we know, dogs and wolves are pack animals. Dogs have evolved to accept humans as members of their packs. Wolves have not. A hybrid raised as a family dog is likely to be lonely. Loneliness will increase its tendency to display other behavior problems I spoke of earlier.

There are several sanctuaries for wolves and wolf hybrids around the country. Sadly, their new residents are often surrendered by people who thought one of these beautiful animals would be perfect in their home. Often they realize too late that they have to change their lives radically to accommodate their pet, a change that is satisfactory to neither human nor wolf. It seems more reasonable for us to stick with the animals who chose us. After all, they come in a wide variety of shapes, sizes, and personalities, just to fit our specific needs and desires.