October 2005

Three Legs and a Spare

by Christie Keith

It was just another night. I walked and fed the dogs, ate my dinner, watched some TV, checked my email, and got ready for bed.

Just another night, except that when my deerhound Raven came to bed, she was "carrying" her left rear leg.

It was somewhat mysterious, because she´d been fine on the evening walk and now she was completely lame. And worse, she was clearly in terrible pain, as she couldn’t lie still at all, tossing and turning on the bed even after I gave her pain medication. Her leg was slightly swollen below her hock, but not hot, and even though she wouldn’t bear weight on it she exhibited no pain when I felt it.

That was the moment everything changed, but I didn’t realize it at first. Neither did Raven’s vet, who thought it might be a cruciate ligament tear and suggested I see an orthopedist. But when I did, he wasn’t under any illusions. I saw his face when he looked at her x-ray, before I looked at the image myself. They call it the starburst pattern, that outward explosion of the bone.

"We’d need a biopsy to be sure," he said. "But this is osteosarcoma. Bone cancer."

What I heard was, your dog is going to die.

All our dogs are going to die, of course. For some incomprehensible reason we thought it was a good idea to take into our hearts an animal capable of the most enormous love and loyalty but who rarely lives much beyond a decade and a half, if that. Human beings can be idiots. And unlike parents who have to love all their children the same, I do have favorites among my dogs, and Raven is the one. She sleeps on my bed every night, while the other dogs make do with sofas and dog beds. I wanted my expected number of Raven’s days, and I just found out I wasn’t going to get them. Or was I?

A decision for life

After posting Raven’s diagnosis to Deerhound-L, I got an email from an AKC judge who breeds Scottish Deerhounds and has been a judge at Westminster. She told me about one of her dogs who had his leg amputated after an osteosarcoma diagnosis, at age six. Raven’s age. He lived to be 12, she said, and died of a heart problem.

That was the very first moment since that x-ray went up on the wall that it occurred to me Raven might not die of this.

Do you know the number one way that osteosarcoma kills dogs? It’s not the tumor itself. It’s not metastases to the lungs. It’s not the spread of the cancer to other bones. It’s because their owners put them to sleep when they can’t control the pain of slowly disintegrating bone. We do not amputate the dog’s leg to treat the tumor. We amputate it to eliminate the pain.

Many people won’t even think about amputating a dog’s leg. A colleague who is a vet told me sadly that at times like that, no matter what she says, they simply don’t hear her. She tells them that dogs do really well with three legs but they don’t listen and their minds are closed.

Other people via osteosarcoma email lists and online support forums report that their vets assure them that amputation doesn’t help, that osteosarcoma is untreatable, and urge them to put their dogs down before they start to suffer. And sometimes they’ve already done it when they find out that osteosarcoma in a dog is not, quite, a death sentence.

Not quite. Colorado State, the Mount Olympus of veterinary cancer care and research, tells us that 15 percent of dogs treated with amputation and chemotherapy never have a recurrence and another 30 percent live two years after treatment. Not great odds, not at all. But not zero.

In fact, some dogs who have been diagnosed with osteosarcoma, then treated with limb amputation and/or chemotherapy, have gone on to normal life spans, dying of other things. Hardly any, it’s true. I don’t mean to give anyone false hope. But these are real dogs, with wagging tails, lolling tongues, one ear up and one ear down. Oh, and three legs.

How much of the terrible prognosis for canine osteosarcoma, the dire statistics, is the result of a human reluctance to turn four-legged friends into three-legged ones?

Three legs and a spare

After hearing about Raven’s diagnosis, a friend of mine with deerhounds, who is herself a human radiation oncologist, got veterinary oncologist Greg Ogilvie to phone me. If Colorado is the Olympus of veterinary oncology, Dr. Ogilvie is Zeus on the mountain. "I heard you wanted some advice without any beating around the bush," he said. Then he told me: amputation, chemo, supplements, diet. Do it all. Do it soon. Dogs, he assured me, are born with three legs and a spare. She’ll be fine as a three-legged dog.

A dozen other deerhound owners told me the same, writing me earnest emails about their threelegged dogs, about how they ran and played and went to the park on three legs. About the early adjustment period, which is sometimes rough. They not only prepared me for the worst but assured me that there is a promised land of three-legged doggedness, where deerhounds are just as unlikely to retrieve a thrown ball as when they had four legs, but will still run after it if you are dumb enough to throw it.

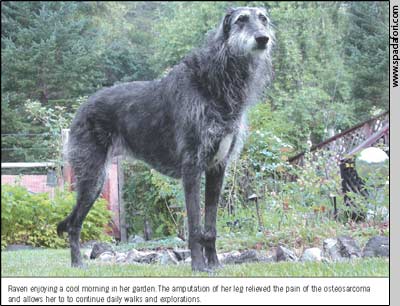

On June 10, Raven’s leg was amputated. It was rough going, as she suffered a post-surgical aspiration pneumonia that nearly killed her. She was in the care of my friend, internal medicine specialist Helen Hamilton, in Fremont. Helen brought her through after five days in the hospital and the surgical removal of my entire life savings. After that bad start, things got better. Even before Raven’s stitches were out, she was running and using the stairs. I’d been cautioned about post-amputation depression that some dogs experience. We never saw it. She seemed so incredibly happy to have that useless, painful leg gone, to be off the pain medications that upset her stomach and fogged her brain.

"Think about how a female dog pees!" one email correspondent had beseeched me after I posted to the deerhound email list. "Don’t mutilate your dog just to keep her a little longer!"

Raven just moves one of her front legs back a little to form a stable tripod when she urinates. Problem solved.

Moving her bowels took a bit more practice. She sometimes had to take a step or two in the middle of it as she lost her balance, and once or twice sat somewhat unexpectedly. She always positioned herself next to the fence, although she never actually leaned on it. After a few days, she got the hang of pooping, too, and that was the last of the real hurdles.

I’m becoming very annoying on the various email lists and forums I’m on, begging people not to decide against amputation for their dogs. I’ve read about dogs with hip dysplasia doing well after amputations, about dogs who weigh over 200 pounds doing well, of dogs whose owners and vets swore they couldn’t function on three legs who are out in the yard running and playing as their owners report the miracle to the other list members. Having seen what I’ve seen, I can’t help being a little pushy about this. However long it lasts, if what you want is quality of life, this is it. Unless your dog already only has three legs, odds are he or she really will adapt after amputation.

The cancer part

Which leaves us with the part of the story that doesn’t have an ending yet, happy or otherwise. The cancer part.

Once you overcome the amputation issues, you are faced with the real enemy. In humans, the quite-substantial pain of bone cancer alerts us that something is wrong at a far earlier stage than with cancer in dogs. Nearly always, by the time the bone lesion is discovered in a dog, the cancer has already spread, usually to the lungs. Even when lungs look clear on an x-ray, microscopic tumors may already be growing.

When Dr. Ogilvie talked to me about Raven, he told me there are only three things that matter when discussing cancer treatment in dogs: quality of life, quality of life, and quality of life. So, that is the guideline I use when making decisions for her care. My happy, active, three-legged dog is having chemotherapy every three weeks. So far she has not had any side effects, has not even missed a meal. If an herb or vitamin or drug upsets her stomach, we do not use it. If she starts reacting to the chemo, we’ll stop it. And if the day comes when she is in pain or suffering, and I can’t help her, then I will let her go.

It’s hard to imagine letting her go, though, while she trucks around this place like she had been born with three legs. When she barks at me for not fixing her dinner quite fast enough. When she trots over to me when I’m working at my computer, and gets me to accompany her into the next room as if she needs me to let her out. Instead, she looks confidently at me, then at her brother Rebel sleeping on the couch, and back at me, saying more plainly than words that she expects me to roust him from his nap so she can have his spot.

Running in her dreams

Raven and I have become so close through all this. I helped her move around before her surgery, when even changing positions caused her agony. I carried her, all 110 pounds of her, when she needed to be carried. I fought all her battles and protected her. I worked with vets, asked for help and did everything that Raven could not do for herself. Through it all, she trusted me, never seemed to doubt that I’d be there to catch her if she fell.

Sometimes at night I watch her running in her sleep, her amputated leg gathering and releasing with the other as she courses after a deer in her dreams. Other times I sit on my back deck watching her hitchgallop around the meadow, playing with my other dogs, sniffing the ground, eating blackberries off bushes and pulling apples off trees with her mouth.

She may not be able to keep up with the pack anymore, may never again scare up a jackrabbit and fly after it like the wind again, never put four legs to the ground and then into the air in the flying gait that is the hallmark of her breed. That wasn’t something that she lost because I had her leg amputated, as some ignorant or unkind people had told me when I made the decision. Cancer took that away from her, not the surgeon and certainly not me.

Will Raven be one of the 15 percent of dogs treated with amputation and chemotherapy who never has a recurrence of her cancer? Or will she be one of the 30 percent who makes it to two years? Obviously we fervently wish her to fall into the 15 percent category. Maybe all we will get is two years or a year, or even a few months, of dreaming about the hunt and hitchgalloping around the meadow, of me watching her flying after a deer in her sleep. I don’t know.

But I know one thing: dead dogs don’t play, or run, or dream. Raven does. She’s happy. And as long as that’s true, so am I.

Information about Osteosarcoma

Osteosarcoma is the most common bone cancer in dogs. Some of the breeds most affected by this form of cancer are racing greyhounds, Rottweilers, Golden Retrievers, and Great Danes, and while it most frequently strikes large and giant breed dogs, any dog can get osteosarcoma.

Osteosarcoma usually forms in the bones of the leg, although it can affect any bone, even the skull. It is believed to originate deep within the bone and is extremely painful. Amputation in dogs is done primarily as a method of pain control, and also to prevent the weakened bone from breaking, a condition known as a pathologic fracture. Pathologic fractures do not heal.

Many dogs show no signs of the tumor until their limb fractures, while others experience intermittent limping, with or without swelling, over a course of several months. Diagnosis is often delayed as the signs can be vague and resemble injuries, muscle strain, arthritis, or cruciate ligament tears.

Christie Keith maintains an osteosarcoma resources page on her web site:

Other recommended online resources:

- Canine Osteosarcoma, Is There a Cure?

- www.vin.com/proceedings/Proceedings.plx?CID=WSAVA2002&PID=2700

- Bonecancerdogs Mailing List

- groups.yahoo.com/group/bonecancerdogs

- Osteosarcoma in Dogs

- www.veterinarypartner.com/Content.plx?P=A&S=0&C=0&A=1035

- Christie also chronicles Raven’s story on her blog:

- www.doggedblog.com/doggedblog/raven/